The population of Indonesia’s endemic songbirds, particularly on the island of Java, has declined sharply due to hunting and trade activities.

Pasuruan, East Java (Indonesia Window) — The once-widespread practice of songbird competitions in many areas of Indonesia has left serious consequences for

wildlife conservation.

The population of Indonesia’s endemic songbirds, especially on Java, has plummeted as a result of intensive hunting and trade activities. However, efforts to conserve those endangered species are still considered highly possible.

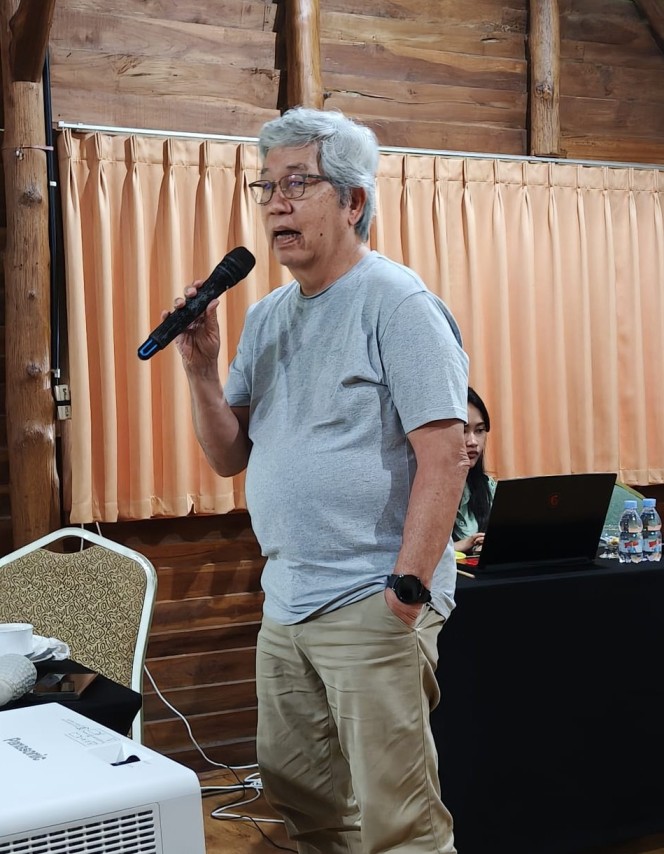

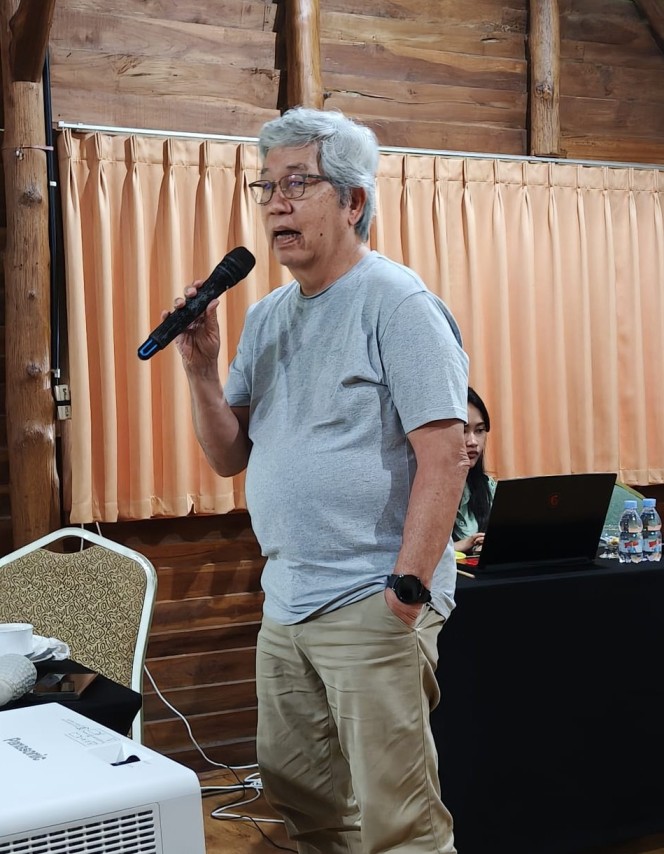

Commissioner of PT Taman Safari Indonesia (TSI), Tony Sumampau, made the remarks during a FOKSI (the Indonesian Wildlife Conservation Forum) Media Trip to the Prigen Conservation Breeding Ark (PCBA) in Prigen, Pasuruan district, East Java province, on Thursday (Dec. 18).

Commissioner of PT Taman Safari Indonesia (TSI), Tony Sumampau, made the remarks during a FOKSI (the Indonesian Wildlife Conservation Forum) Media Trip to the Prigen Conservation Breeding Ark (PCBA) in Prigen, Pasuruan district, East Java province, on Thursday (December 18, 2025). (Indonesia Window)

“Songbird competitions used to be very popular and are now gradually declining. But the impact is already evident—the bird population has dropped drastically,” Tony said, emphasizing the importance of education so that young people do not repeat the same mistakes made by previous generations.

According to Tony, the songbird crisis in Southeast Asia has drawn international attention and was even discussed in Singapore during the Southeast

Asian Songbird Crisis Summits in 2015 and 2017.

At those forums, he continued, Indonesia was cited as one of the countries experiencing the largest decline in the songbird population in the world, driven by massive hunting practices.

Amid this crisis, PCBA has taken an active role through captive breeding and reintroduction programs.

“At PCBA Prigen, there are currently 255 bird cages dedicated to conservation, along with more than 50 enclosures at Taman Safari Bogor (the safari park in Indonesia’s Bogor district, West Java province). This shows that Indonesia is fully capable of breeding, increasing the population and then releasing birds back into the wild,” Tony explained.

Several songbird species have been released at different locations. In Bogor, Taman Safari Indonesia (TSI) released black-winged starling (Acridotheres melanopterus); in Prigen, Javan pied starling (Gracupica jalla); and in Bali, the iconic Bali myna (Leucopsar rothschildi).

The results have been significant. The population of Bali mynas has now exceeded 600 individuals, surpassing the target of 500, Tony said. “Its status should be downgraded—it should no longer be classified as critically endangered. In Bali, even 40 Bali mynas could be found in a single tree,” he noted.

Tony stressed that conservation efforts are never too late. The biggest challenge lies in how to raise awareness, particularly among children and younger generations, about the importance of protecting nature.

He added that conservation institutions that promote animals to the public also bear a moral responsibility. “From these activities, we can allocate part of the benefits to raise public awareness about the importance of the environment and nature,” he said.

Tony also underscored that a sustainable environment cannot exist without both wildlife and plants. TSI, he said, has proven this by rehabilitating former Dutch-era tea plantations that had become unproductive.

“Now these areas have turned back into forests and are favored by birds and other wildlife,” he said.

When vegetation thrives and the environment becomes suitable, wildlife would return naturally. Nevertheless, Tony acknowledged that the planting of Java’s endemic tree species has not yet been pursued seriously. “If someone starts it, we will certainly support it,” he said.

Reporting by Indonesia Window

.jpg)